Hui Lin

2017-03-25

What is data science?

Data science and data scientist have become buzz words. Allow me to reiterate what you may have already heard a million times in the media: data scientists are in demand and demand continues to grow. A study by the McKinsey Global Institute concludes,

“a shortage of the analytical and managerial talent necessary to make the most of Big Data is a significant and pressing challenge (for the U.S.).”

You may expect that statisticians and graduate students from traditional statistics departments are great data scientist candidates. But the situation is that the majority of current data scientists do not have a statistical background. As David Donoho pointed out:

“statistics is being marginalized here; the implicit message is that statistics is a part of what goes on in data science but not a very big part.” ( from “50 years of Data Science”).

What is wrong? The activities that preoccupied statistics over centuries are now in the limelight, but those activities are claimed to belong to a new discipline and are practiced by professionals from various backgrounds. Various professional statistics organizations are reacting to this confusing situation. (Page 5-7, “50 Years of Data Science”) From those discussions, Donoho summarizes the main recurring “Memes” about data sciences:

- The ‘Big Data’ Meme

- The ‘Skills’ Meme

- The ‘Jobs’ Meme

The first two are linked together which leads to statisticians’ current position on data science. We assume everyone has heard the 3V (volume, variety and velocity) definition of big data. The media hasn’t taken a minute break from touting “big” data. Data science trainees now need the skills to cope with such big data sets. What are those skills? You may hear about: Hadoop, system using Map/Reduce to process large data sets distributed across a cluster of computers. The new skills are for dealing with organizational artifacts of large-scale cluster computing but not for better solving the real problem. A lot of data on its own is worthless. It isn’t the size of the data that’s important. It’s what you do with it. The big data skills that so many are touting today are not skills for better solving the real problem of inference from data.

Some media think they sense the trends in hiring and government funding. We are transiting to universal connectivity with a deluge of data filling telecom servers. But these facts don’t immediately create a science. The statisticians have been laying the groundwork of data science for at least 50 years. Today’s data science is an enlargement of traditional academic statistics rather than a brand new discipline.

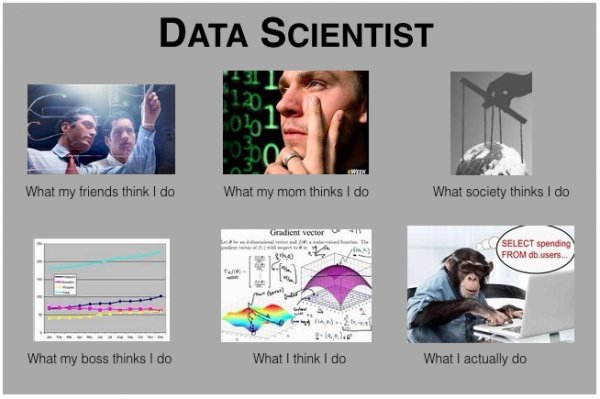

This question is not new. When you tell people “I am a data scientist”. “Ah, data scientist!” Yes, who doesn’t know that data scientist is the sexist job in 21th century? If they ask further what is data science and what exactly do data scientists do, it may effectively kill the conversation.

Data Science doesn’t come out of the blue. Its predecessor is data analysis. Back in 1962, John Tukey wrote in “The Future of Data Analysis”:

For a long time I have thought I was a statistician, interested in inferences from the particular to the general. But as I have watched mathematical statistics evolve, I have had cause to wonder and to doubt. … All in all, I have come to feel that my central interest is in data analysis, which I take to include, among other things: procedures for analyzing data, techniques for interpreting the results of such procedures, ways of planning the gathering of data to make its analysis easier, more precise or more accurate, and all the machinery and results of (mathematical) statistics which apply to analyzing data.

It deeply shocked his academic readers. Aren’t you supposed to present something mathematically precise, such as definitions, theorems and proofs? If we use one sentence to summarize what John said, it is:

data analysis is more than mathematics.

In September 2015, the University of Michigan make plans to invest $100 million over the next five years in a new Data Science Initiative that will enhance opportunities for student and faculty researchers across the university to tap into the enormous potential of big data. UM Provost Martha Pollack said:

“Data science has become a fourth approach to scientific discovery, in addition to experimentation, modeling and computation,…”

How does the Data Science Initiative define Data science? Their website gives us an idea:

“This coupling of scientific discovery and practice involves the collection, management, processing, analysis, visualization, and interpretation of vast amounts of heterogeneous data associated with a diverse array of scientific, translational, and interdisciplinary applications.”

With the data science hype picking up stream, many professionals changed their titles to Data Scientist without any of the necessary qualifications. But at that time, the data scientist title was not well defined which lead to confusion in the market, obfuscation in resumes, and exaggeration of skills. Here is a list of somewhat whimsical definitions for a “data scientist”:

- “A data scientist is a data analyst who lives in California”

- “A data scientist is someone who is better at statistics than any software engineer and better at software engineering than any statistician.”

- “A data scientist is a statistician who lives in San Francisco.”

- “Data Science is statistics on a Mac.”

There is lots of confusion between Data Scientist, Statistician, Business/Financial/Risk(etc) Analyst and BI professional due to the obvious intersections among skillsets. We see data science as a discipline to make sense of data. In order to make sense of data, statistics is indispensable. But a data scientist also needs many other skills.

In the obscenity case of Jacobellis v. Ohio (1964), Potter Stewart wrote in his short concurrence that “hard-core pornography” was hard to define, but that “I know it when I see it.” This applies to many things including data science. It is hard to define but you know it when you see it.

So instead of scratching my head to figure out a one sentence definition, We are going to sketch the history of data science, what kind of questions data science can answer, and describe the skills required for being a data scientist. We hope this can give you a better depiction of data science.

In the early 19th century when Legendre and Gauss came up the least squares method for linear regression, only physicists would use it to fit linear regression. Now, even non-technical people can fit linear regressions using excel. In 1936 Fisher came up with linear discriminant analysis. In the 1940s, we had another widely used model – logistic regression. In the 1970s, Nelder and Wedderburn formulated “generalized linear model (GLM)” which:

“generalized linear regression by allowing the linear model to be related to the response variable via a link function and by allowing the magnitude of the variance of each measurement to be a function of its predicted value.” [from Wikipedia]

By the end of the 1970s, there was a range of analytical models and most of them were linear because computers were not powerful enough to fit non-linear model until the 1980s.

In 1984 Breiman et al. introduced classification and regression tree (CART) which is one of the oldest and most utilized classification and regression techniques. After that Ross Quinlan came up with more tree algorithms such as ID3, C4.5 and C5.0. In the 1990s, ensemble techniques (methods that combine many models’ predictions) began to appear. Bagging is a general approach that uses bootstrapping in conjunction with any regression or classification model to construct an ensemble. Based on the ensemble idea, Breiman came up with random forest in 2001. Later, Yoav Freund and Robert Schapire came up with the AdaBoost.M1 algorithm. Benefiting from the increasing availability of digitized information, and the possibility to distribute that via the internet, the tool box has been expanding fast. The applications include business, health, biology, social science, politics etc.

John Tukey identified 4 forces driving data analysis (there was no “data science” then):

- The formal theories of math and statistics

- Acceleration of developments in computers and display devices

- The challenge, in many fields, of more and ever larger bodies of data

- The emphasis on quantification in an ever wider variety of disciplines

Tukey’s 1962 list is surprisingly modern. Let’s inspect those points in today’s context. There is always a time gap between a theory and its application. We had the theories much earlier than application. Fortunately, for the past 50 years statisticians have been laying the theoretical groundwork for constructing “data science” today. The development of computers enables us to calculate much faster and deliver results in a friendly and intuitive way. The striking transition to the internet of things generates vast amounts of commercial data. Industries have also sensed the value of exploiting that data. Data science seems certain to be a major preoccupation of commercial life in coming decades. All the four forces John identified exist today and have been driving data science.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.